The Construction of Space Shuttle Launch Complex 39-B

A very personal and technical written and photographic history, by James MacLaren.

Page 63: Creeping 79K24048 as Backdrop For A Shuttle Landing Family Day at the Pad, and a Lot of Centaur Porch.

| Pad B Stories - Table of Contents |

This one should be grouped with the other Home Life pages where the untellable joy of a small child can be found, except that it shouldn't, because it contains information that can be found nowhere else in the world, documenting a precise snapshot in time of the construction sequence for the Launch Pad, and for that reason, I'm placing it here, in the main body of the narrative.

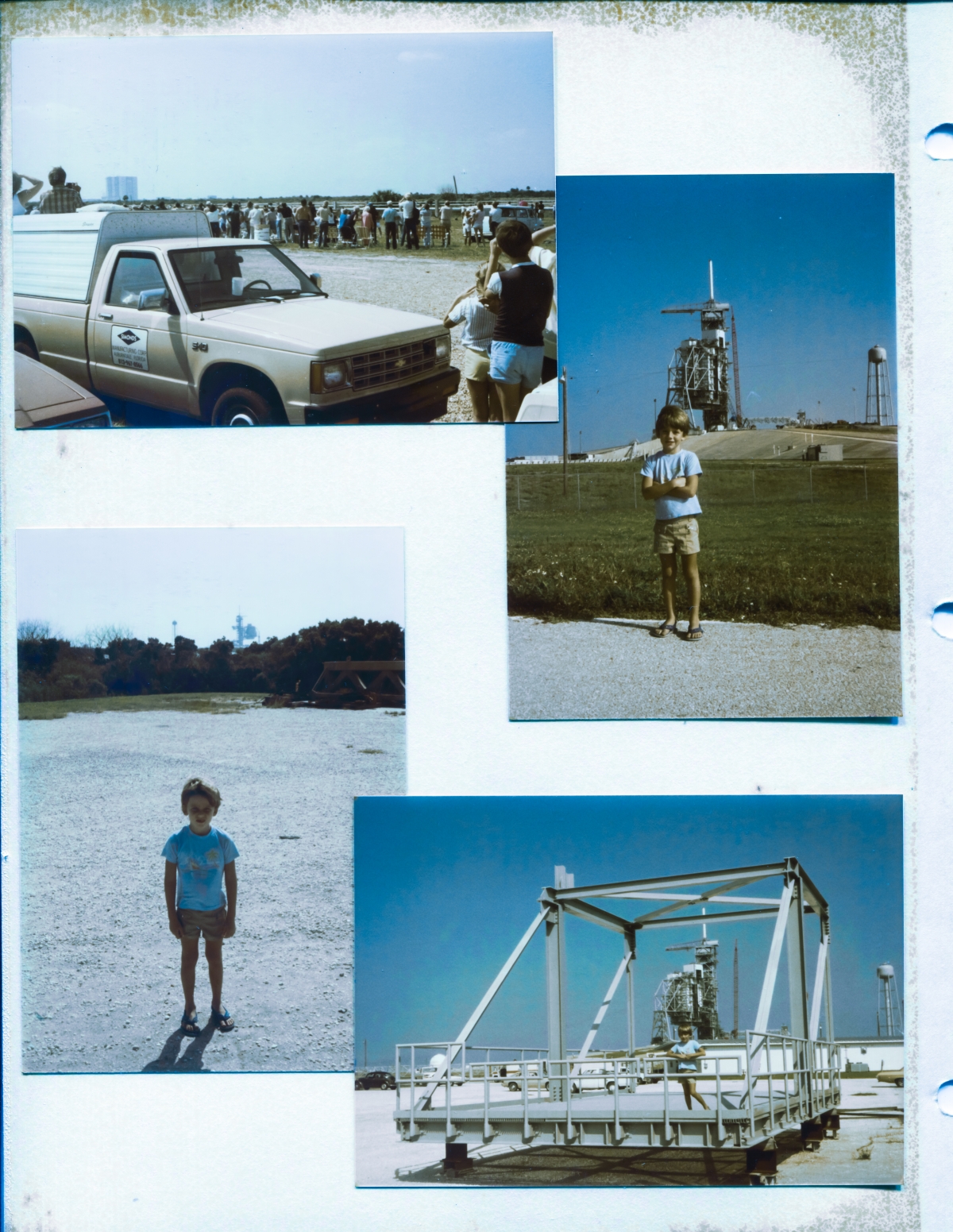

We will be examining each individual photograph you see in the image above, in detail. Each one stands alone and has a separate story to tell, but the four of them also braid their stories together into a larger and much more encompassing whole, and I will begin with some background to tell you how we wound up together at this place on this day, using the top left image on the Photo Album page you're seeing here.

And here below, just that photograph. Click it for full size, but it's otherwise unaltered.

You are looking directly at, just a little bit left of center, ever so slightly below the level of the top of the VAB, the second time ever that a Space Vehicle, initially placed into an operational mission orbit, returned to its launch site at the close of that mission.

Despite what the low quality of this image might cause you to think, Challenger was plainly visible, and had been so since before it entered its heading alignment circle, and you look at all the people in this image, and every single one of them (with the exception of a single elderly woman in the process of getting up out of her chair to gain a better view) is eyes-riveted to the incoming spaceship skimming lightly downward above the far horizon there before them.

This was a really Big Deal when it happened.

We were out there for the first return to launch site, too, and that was beyond overwhelming, but I have no photographs from that gloriously calm and benign February morning when I held Kai up in my arms, to get him eye-level above the crowd of people up on the Pad Deck where he could see clearly and unobstructedly (they let us up on top of the Pad for that one incredibly enough, the only time they ever did it, mothers, fathers, children, everybody, all behind white temporary picket fencing to keep us out of the Flame Trench and out from directly beneath the RSS, but otherwise it was a fucking throng of people up there on top of the Pad) and together we watched Challenger inbound as a tiny pure white winged apparition coming in from the west which grew as it flew, taking a left heading alignment circle against the clearest and sharpest blue early-morning sky imaginable, and then, incredibly, it passed through the open framework of the RSS's Primary Framing, heading right to left as we stared upwards at it in gobsmacked disbelief, watching it angle downwards at a too-steep slope, at a too-fast speed, and the sonic boom came without warning and it was LOUD and then Challenger flared out just as pretty as you please over the distant treeline inbound for runway 15, and then it was down, and then it was over, and then everybody went crazy!

Words cannot take us to that place. Words are of no use at all for that place.

Returning to the narrative of this day, we affix a hard date of October 13, 1984, to all four of our photographs, and even a time accurate to within a minute, of 12:26pm (it was still Daylight Savings Time that day) for our image showing Challenger still in the air, just about to touchdown on the runway at the Shuttle Landing Facility. The other photographs will be addressed in the sequence they were taken, and the whole series takes up perhaps one full hour after Challenger went wheel-stop on the concrete, perhaps a bit more than that, on a quite-warm and slightly hazy Fall day in Florida.

And it was the Landing, and the one-day permission given by NASA authorities for badged employees to bring their families out to the facility to see for themselves what their wives and husbands, parents and children, were doing out there, in a closed area, otherwise utterly forbidden entry to, which brought us to this place at this time.

And now you understand how these photographs came to be.

And we never missed a chance, when an opportunity to do so was presented to us.

We could never get enough of it.

Ever.

The image above, "showing" Challenger, is no damn good at all.

Here it is again, greatly enhanced for contrast to cut through the haze and let you see the location of a distant, tiny, thing.

Needless to say, the extreme enhancement for contrast on a forty-year-old print photograph taken from an album, which was scanned to create the image you see, enhances everything, including no end of blemishes and flaws, and Challenger remains near-impossible to sort out from all of the other background noise and defects, so I'm going to label this photograph and place an arrow on it to allow you to precisely locate Challenger, and you can see that when you click this link. Fortunately, the area of the photograph with Challenger visible in it contains no other significant blemishes, flaws, or enhancement artifacts, and once you know where it is, it's not only quite easy to see, you can also tell that it's in a very-nearly level orientation, coming out of preflare, just before they pitch the nose up and lower the landing gear prior to touchdown.

And there A Day was had, there that day.

And they all departed when it was over.

Except for me and a brilliantly-shining six-year-old Kai.

You should already know full well from having read what has come before this page, that when I was with Kai in a place like this, I was prone toward bending things a little. Prone toward crossing invisible lines a little. Maybe even a lot. Prone toward a fuller, fullest, appreciation of the exotics, the phenomena, the totems, the mana, filling this world all around us there with their potent invisible energy.

And it was no different this day, and with an empty gravel parking lot there just south of the Ops Building, and not a single soul showing any interest in us at all, official or otherwise, or even being visible in the first place, we...

Drank a little deeper of it...

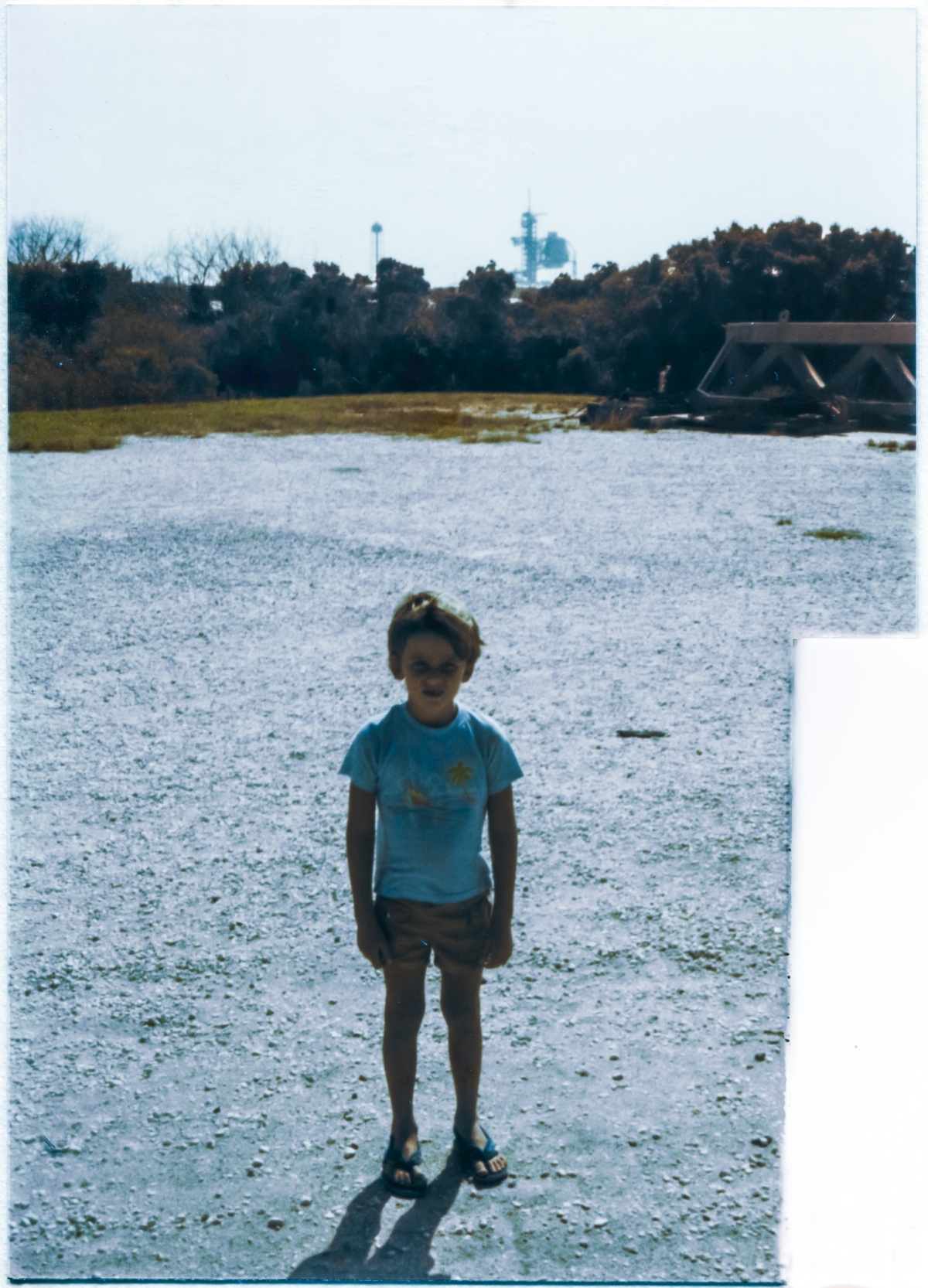

This is not a very good photograph. In order to frame Kai with Pad A (where STS-41G had departed from on a volcanic pillar of flame only eight days previously) in the distance behind him, I was forced into shooting his shadowed side, against a blazingly sunlit gravel parking lot out there south of the Ops Building. But it was important enough to me at the time, that I asked him to stand there for a few moments in the swelling noontime heat, and although the look on his face clearly telegraphs the fact that he has other places he'd rather be, he was his usual sterling self, and obliged his father, yet again, and I got my photograph, poor lighting and all.

Just off the gravel to his right, inscrutable heavy equipment lies unattended.

I do not know what this is, or what it was used for, but it has a look to it of perhaps being involved with lifted weight proof testing, or perhaps fit-checking of some kind, or perhaps it's a very sturdy spreader bar or strongback, and whatever else it might be, one thing for sure is that it is... robust. That upper horizontal member is heavy tube steel, and the very-closely-spaced diagonals beneath it are also very heavy tube steels, and the whole thing has got to be extraordinarily rigid and strong.

But what it might have been used for, I cannot know.

It was not any of our stuff, that's for sure.

And you'd be wandering around out on the Cape, doing whatever, wherever, and you'd oftentimes come across this kind of stuff, laying there in the grass on cribbing, or maybe over in a far corner of some parking lot near some anonymous building or facility, utterly unidentified, showing clear signs of not having been so much as touched in literal years, and you'd scratch your head and wonder what it was, and never an answer would come.

NASA had no end of this kind of stuff sprinkled around, here and there.

Whatever it was, it needed to be very strong and rigid, and it was out at the Pad, and on the Pad no end of exceedingly heavy things got worked with and worked on, and...

I dunno.

Look close, and you can see a quite-hefty sheave block and swivel hook on the cribbing in front of it, and...

...we'll never know.

Ok.

No one is coming. No one is around. No one seems to care.

Let us head on over to something that's a lot more interesting, shall we?

Let us head on over to the Centaur Porch.

Kai knows exactly what it is, exactly where it will be going on the towers, exactly what it will do when it gets there, and exactly what it will feel on Launch Day, and... it doesn't get any better than this.

Actual launch pad hardware, that his own father would be involved in the erection of, and he is standing directly upon it, and he knows that in the not-too-distant future, his footprints upon it will share in the incredible violence it will witness and endure whenever a Space Shuttle departs.

And we had the whole place to ourselves at the time, to savor, to relish, to marinate ourselves in. No, it really does not get any better than this.

But...

There was a darkness about it, too. And despite the way it may have presented itself to the bright eyes of a fascinated and beyond-happy six-year-old, it presented itself in other ways to other eyes.

My own included.

Don't get me wrong, the Centaur Porch was cool as hell, on several different levels, and I always thought it was cool as hell, and it's always been one of my favorite little out-of-the-way places on the towers...

But what this thing represented scared the living fuck out of me every time I thought about it.

It was yet another manifestation of how hard they were pushing themselves into the abyssal depths of pitch-black unknown territory...

Using in part, 79K24048 to do so...

Holding a candle ahead of themselves, giving off a tiny light, flame wavering in a frighteningly-chill breeze...

Thinking they could... see.

Believing they could see.

Believing they could pierce the darkness that enveloped them all around.

Shuttle Centaur was...

...madness.

And they were proceeding with it, believing themselves... sane.

So I suppose that before I can return to the image of a bright-eyed six-year-old feet-down on the steel structure of the Porch itself, I'm going to need to do a little background fill-in work bringing you up to speed on...

...Shuttle Centaur.

And I have glancingly exposed you to some of this already, but I was very very coy about it, and was careful to not explicate. To not follow the implications. This has been an extraordinarily heavy narrative up to this point, and the addition of any extra weight as we wended our way along was not...

...advisable.

Too much.

Far far too much.

But now...

And to understand Shuttle Centaur, we must back up all the way to Atlas Centaur, which is where all things Centaur originate from, and The Tale of Centaur is a remarkably long and braided thing with many differing branches and pathways, intersecting differing launch vehicles in many places, in many ways, extending down through time all the way to the present day.

Centaur was the first-ever attempt at a hydrogen-fueled upper stage for a rocket, and it was eventually flown atop Atlas (all major versions), Titan (III and IV), and Saturn I launch vehicles, in addition to being proposed, with design, development, and production of flight hardware entered into, for the Space Shuttle.

And as of the time of this writing in late 2023, Centaur yet lives, and will continue to fly on Atlas V until the end of that program, and sometime soon (they hope) it will start flying on ULA's Vulcan.

Centaur is all over the place, and it's hard to get away from when you start looking into the various space launch systems designed and implemented by the United States.

When it was first imagined, proposed, and developed back in the 1950's, Centaur was radical.

Liquid Hydrogen is some pretty bad-ass stuff, and I've already discussed it before in this narrative in more than one place, and I'm not going to be repeating any of that now, but... especially back in the 1950's ...holy shit!

They proposed to create an exceedingly high-energy (for the time) Upper Stage which would allow them to increase payload mass significantly, without significantly increasing the mass of the launch vehicle which would be propelling it into space.

The underlying physics behind the desire to use liquid hydrogen as a rocket propellant was well understood at the time, as can be seen by reading this master's thesis entitled Liquid Hydrogen - High Energy Rocket Fuel by United States Navy Lieutenant Eugene A. Cernan (last U.S. astronaut to leave footprints on the Moon as part of the Apollo Program) which was written in 1963.

But the application of that physics... as expressed in high-precision metal forms handling exceedingly-volatile liquids that are cold beyond imagining and which will boil furiously at temperatures in the hundreds of degrees below zero Fahrenheit, prior to running them through very high-pressure turbomachinery and igniting them, and then precisely controlling that ignition... not so much.

Hydrogen is a right bastard to work with, and in the beginning they were really reaching, and nobody was entirely sure that their reach wasn't exceeding their grasp.

And Centaur emerged from the sheets of paper it was originally conceived upon in the form of a ridiculous stainless-steel balloon, and...

That didn't go over all so very well in certain quarters, but it was eventually caused to work, and it went on to become more or less standard issue equipment for propelling numerous payloads in numerous places, but up until Shuttle Centaur, none of those places also carried human crew, and none of them required intact abort capability (which itself was ludicrous, but it drove the design), and none of them were enclosed within a confined Payload Bay that would perforce need to remain enclosed during the full term of any intact abort that might, god forbid, have to be invoked during initial ascent, and even after a successful ascent to orbit, the Centaur would linger there inside the Payload Bay, live, not enough meters from the crew, which was also live, to even bother counting, until the Payload Bay Doors could be opened, after which, following additional time spent in preparation and preflight checkout, it would be kicked out of the Payload Bay, allowing the Shuttle to get the hell away from it, prior to the ignition of its RL-10 engines, and during all of that time...

...it was a ticking time bomb.

And oh hell, why not, let's pretend that it all worked perfectly during an abort. Everything did exactly what it was supposed to do. They actually managed to fluid-dump the Centaur on the way back in, and the weight was brought down far enough to allow the Orbiter to make a proper touchdown on the runway without collapsing a landing gear or blowing tires and yawing off into one of the ditches alongside the runway and pissing off the alligators in there, and it rolls out, and it goes wheel-stop, and it's now just... sitting there... except that it's not, and although oh-so-very-much of the LOX and LH2 originally carried by the Centaur went overboard... not all of it did (or could), and now here we are, sitting in the Crew Cabin, getting unhooked, considering whether or not we should just open the hatch and jump down to the concrete before the support caravan arrives, and take our chances with broken legs and any OMS or RCS hypergol that might still be venting, because the goddamned Centaur was also going to still be venting, and it was going to be venting boiled-off residual LOX and LH2 in the form of GOX and GH2, and that's a pretty nasty combination of things to be dealing with in person, and there's hot TPS Tiles, and hot Brakes, and hot APU's back there also still venting, and fuel and oxidizer and some sort of hot ignition source is all you need, right... and who knows if something else is going to choose this exact wrong time to put off a spark or two... and if the whole thing goes up exactly like the goddamned Hindenburg went up while we're still inside of it... well... that's not going to be very good...

...and...

And there were many voices raised against the whole concept of Shuttle Centaur, including more than just a few of the astronauts who might wind up flying with the thing, but in the end, they proceeded with it anyway. And you find yourself reading a lot of the technical documentation that surrounds it, and you stop and realize that there's something about the tone of so much of this stuff...

...that isn't quite right.

There exists a deeply-frightening type of glossing-over confidence in too many places.

And you suddenly feel yourself realizing that at this exact same time, in other places, with other technical and management teams, that exact same glossing-over confidence was steadily propelling everyone, smoothly and serenely, directly toward the events that were to burst upon them one and all, beneath the Cold Florida Sky of January 28, 1986.

There was systemic disconnect, disjoint, disbelief...

And there in the darkness of the gap that existed between confidence and hardware...

Evil things were growing...

...unseen.

And Shuttle Centaur consisted in an enormous two-part balloon, made of thinnest stainless-steel, utterly incapable of supporting its own weight unless pressurized, filled up with liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen, pushed by a pair of rocket motors on its bottom, and come Launch Day, it would need to be filled up, to be fueled, and although that might sound like a simple enough thing to arrange, when you're dealing with this stuff out on the launch pad, nothing is simple anymore, and the apparatus they devised for the purpose of fueling the Centaur which was sitting there inside the Space Shuttle, was... yet another thing that was not well-received in certain quarters (many of us out at the Pad dutifully did our parts in the furnishing and installation of this stuff, but we HATED it, even as we continued to work on it), and our Centaur Porch is what that poorly-received apparatus was going to be sitting on top of, directly connected to the fully-fueled Space Shuttle, right on up to the instant the Holddown Bolts blew, and it started violently clawing itself up and away from the Pad.

And the Porch, with the Centaur's Rolling Beam Umbilical System (RBUS, pronounced "arbus") apparatus (we'll get to it in plenty of detail soon enough, but not right now, ok?) that sat on top of it, was only the far end of an entire GSE (Ground Support Equipment) system reaching back from the T-0 disconnect Carrier Plate attached on the left side of the Orbiter's fuselage which interfaced with a reworked PBK (and I marvel at how the never-used elements of that whole Payload Bay Kit system managed to thread themselves down through time into so many disparate things... and places... and... stories) penetration which gave access to Centaur LH2 plumbing inside of the Payload Bay, back there just forward of the Aft Compartment and the Left OMS Pod, heading from there, all the way back to the LH2 Dewar which sat out near the Pad Perimeter Fence.

On the LOX side, it was significantly different, and we learn in "Rolling Beam Umbilical System" by Bemis C. Tatem Jr., Planning Research Corporation, Kennedy Space Center, Florida, on Page 2 of that document that they could have gone with running LH2 through the TSM but "Necessary additional lines would be added to the existing TSM's carrier plates as depicted in figure 1. Lines would be routed down the service masts as shown in figure 2. An overriding disadvantage of this approach was its adverse effect on Orbiter flight weight for the LH2 service functions."

No further particulars are given as to exactly why running the LH2 plumbing through the TSM would cause an "adverse effect on Orbiter flight weight" even though the LOX plumbing wouldn't, and I have not been able to dredge up any additional technical documentation about it, so we'll just have to satisfy ourselves with accepting that it was looked at, closely, by competent people, and the reasons were good ones, and so they stayed with Centaur LOX Fill and Drain through the TSM, but went with Centaur LH2 Fill and Drain through the RBUS.

The best, most comprehensive, document I've been able to lay hands on is titled "Centaur G Technical Description, A High-Performance Upper Stage For Use In The Space Transportation System" and it was prepared in January/February 1982 by General Dynamics Convair Division, and those are the people who made the goddamned thing, and it's thorough, but it's not quite thorough enough for the purposes of understanding exactly why they went with the RBUS (which is a whole complete separate system) for Fuel, but stayed with the LOX Carrier Plate on the LOX TSM for Oxidizer.

I will here insert a Scientific Wild-ass Guess (SWAG) which posits that since the LH2 tank inside the Centaur was forward of the LOX Tank, that would involve an unknown (but greater than zero) length of additional plumbing to reach all the way back to tap into the existing LH2 plumbing somewhere in the vicinity of where the TSM provides LH2 to the External Tank through the aft end of the Orbiter. Greater than zero additional plumbing length equals greater than zero additional weight, and somebody, somewhere, decided that they could dispense with that additional by going over the side near the aft end of the Orbiter's Payload Bay. But is any of that true? Probably not. How the fuck am I supposed to know, without sensible documentation, anyway? Fuckem. It's what they did. They had a reason. So ok.

Extracted from that document, here's Figure 3-47, taken from Page 48, which I've marked up some to help with locating yourself, showing you schematic view how the LH2 Fill and Drain lines head off to the side of the Orbiter where the RBUS is, while the LOX Fill and Drain lines head through the rear bulkhead of the Payload Bay into the Aft Compartment, aiming for the LOX TSM Carrier Plate.

And here's a very doctored-up and labeled view of the stuff coming off of the CISS (Centaur Integrated Support System, and no, I'm not getting into that thing. It's in the big Centaur G Technical Description PDF document I just showed you. All you can stand. More than you can stand, even. Drink up.) as an isometric view (but it's not, really, 'cause it's very distorted, even after I beat it as far into submission as I could, and it was rendered quite poorly in the first place anyway, and I don't remember where I got it from, so you're on your own with that end of things, too) showing you all of that new Centaur Plumbing extending into the Aft Compartment, that became a permanent addition to the two orbiters they modified for it (Atlantis and Challenger), which means all of this extra Aft Compartment weight went uphill, every time, on all missions from then on, reducing the payload-weight-to-orbit capabilities by a commensurate amount, and... there's so so very much to not like about this stuff. It's all over the place, in too many different aspects and locations to ever enumerate completely. Sigh.

So ok. Back to the Pad. Back to the towers. Let's start with an overview of the the whole RBUS schmutz. The whole LH2 plumbing system, from all the way out by the Pad Perimeter, and heading inbound from there.

79K24048 sheet M-28 shows us the whole thing, from out past the big LH2 Dewar where the tanker trucks hook into the system to furnish LH2, all the way across and up the Pad Slope till you get to the LH2 Tower, which you've already met and are presumed to already know all about.

79K24048 sheet M-19 elaborates on things a little, and tells us that our Centaur modifications to the system begin just off the LH2 Tower, in the Piping Trench that runs up to it from where it comes up the Pad Slope.

And the place where it all starts is just about as bland and unassuming as you could possibly get with a run of Vacuum Jacketed lines, and all they did was cut a hole in the existing lines and weld a stub piece of pipe to it, where they could then tap off the LH2 they would be needing for Centaur, and feed it on inbound over to where they needed it, or drain it back out to the Burn Pond (I need to work that thing into the story somewhere, too. It was pretty cool. And weird, too.) when they didn't need it.

Pretty boring stuff. Here it is on 79K24048 sheet M-32. Look! Plumbing! Whoo hoo!

And then, once they tapped into the existing system, 79K24048 sheet M-33A shows us how they ran their new LH2 Lines across the North Piping Bridge, and over to the FSS around behind the 9099 Building via the ECS Tower and Platforming, and then, once we get into the FSS, things start happening.

And what started happening was the Centaur Platform, which was treated separately from the Centaur Porch, which bolted directly on to it, and I never did find out why the Porch was handled under a completely separate contract, on a completely separate drawing package (79K26050), and furnished by others, even though the whole deal was erected by Ivey Steel while I was working for them.

I have no fabrication drawings for the Porch, but I have drawings for all the rest of it, and actually I do have something for the Porch, but it's from the Demolition drawings which were used to tear down the RSS and FSS at Pad B.

Let's go look at the Porch on the demo drawing, first.

As you can see on Demo Drawing S-49 Centaur Porch Elevation And Section, there's not much to it, really, but at least you get to see it rendered in reasonable-enough detail, as opposed to what 79K24048 sheet S-51A (and stop a minute, and consider that the drawing which was used to demolish it was of significantly better quality than the drawing which was used to erect it) has to say about the exact same thing, and of course it matches what Kai is standing on, in our photograph above, exactly, so we're in the right place, and we've got the right thing.

And in order for the Porch to attach to the tower, there had to be a Platform for it to attach to, and it turns out that the platform was a pretty fair-sized deal, and involved a fair bit of time and effort to get hung on the tower.

And it started out by wrapping around from the back side of the FSS, with a short stair to give you access to it because it was 4'-3" above the level of the FSS where you got to it from, and then it filled out into a pretty expansive area of steel-bar grating supported by some pretty stout framing, above and below, and it hung out there over empty space in the area of the Struts, and extended all the way to the front side of the FSS, in between the FSS and the Hinge Column, and that's where the Porch got bolted on, and the Porch was cantilevered out toward where the Space Shuttle would be sitting on the MLP when it was rolled out, and the whole thing always looked a little scary to me cause it was so damn close to that Shuttle taking off. Yes, the Stack "walked" north as it lifted off, taking the Orbiter's left wing away from the Centaur Porch, and the Porch didn't quite reach all the way to the wingtip, but still... that damn thing was close.

But they never hit it, so that's nice, right?

And here's 79K24048 sheet S-50 showing you the general arrangement of things in plan view, and I've labeled it to help you visualize it and see where you are, hanging out over open space to the south of the FSS, sitting in the Struts between it and the Hinge Column.

And to make that happen, the existing access catwalk to the Hinge Column Lower Bearing, Lower Access Platform had to get removed, and 79K24048 sheet S-47 calls that one out (and that's it there down in the lower left corner of S-50 in Detail K, too), and if you've forgotten about that access catwalk (but you shouldn't have, 'cause we've been to the damn thing a lot already), well then, here's 79K14110 sheet S-3 to refresh your memory with what got ripped off the tower to allow us to install all that nice new Centaur platforming.

And if all that doesn't get you located... well then... I dunno. I've done all I can with it.

And now that we've got a proper fix on where we are and what we're putting in there, we can go do 79K24048 sheet S-51 and see how we're actually going to be building this thing, and yeah, it's quite the substantial item, and it's threaded in there through the Struts, and other parts of it extend off into other areas, and yeah, there's room for it, but no, there's not a lot of room for it, and the Struts are Primary Framing of course, and will always have the right-of-way of course, and...

And I'm gonna discuss this thing in detail, just to kind of help you get a better feel for it...

And as part of getting a better feel for things, here's our old friend 79K14110 sheet A-1, which we originally met back on Page 4 of this narrative, and it's been mentioned here and there a few times already, but I'm going to stop to repeat, again, the conventions they used to identify which face of the FSS they were showing us on their drawings, because it's tricky, and I've had enough people get lost with this thing, that I feel it incumbent upon myself to hit it again, here and now, before we go any further with our Centaur platforming, and the original sense of the thing was that the east side of the FSS, which faces the Space Shuttle when it's sitting there on the MLP right next to the FSS, is, very reasonably, named FSS Side 1, and again, very reasonably, we name the other sides of the FSS from a point of view of looking straight down on top of it, seeing it in plan view, and we travel clockwise around from Side 1, and we get Side 2, which is the south side, and then Side 3, which is the west side, and which faces directly away from the Space Shuttle sitting there on the MLP, and finally, as we complete our clockwise circuit, we get Side 4, which faces north, and why are you going on and on and ON about this one MacLaren, anyway?

And the reason I'm going on and on and ON, is because, ok, the FSS has a square outline in plan view, and there's four sides to a square, and all well and good, and the four faces of the stupid FSS were NAMED exactly like you'd expect them to be named, 1 through 4, and all well and good...

Except that then they came along and built themselves a nice new RSS and welded it on to the FSS, and when they welded it on they did so via the expedient of creating a Hinge Column, which was rigidly braced using a set of Struts, and the goddamned Struts extended south from the Side 1/2 corner of the FSS, which, ok, kind of now makes them part of FSS Side 1, all well and good, BUT... coming off of the Hinge Column going the other way, headed back to the Side 2/3 corner of the FSS, at an angle to the layout of everything else on the goddamned FSS, you get the rest of the Struts, and no, that's not going to work as "Side 2" of the FSS, which has already been given a name, and is the south face of the FSS, which is a completely different thing and place, distinct and separate from the part of the Struts which runs southeast/northwest, and is now sort of making an additional southwest face on our FSS, and now what are we going to do, and what they did was just shrug their shoulders and call that part of the Struts Side 5, and now you've got this confusing goddamned thing where, when looking at things from the south, you've got a Side 2 sitting there inside of your new side 5, and...

Feh.

And it's simple, but it's also quite devious and when you find yourself working in this area, south of the main body of the FSS, it gets just about as confusing as hell when it comes to getting a rock-solid sense of just exactly which fucking side is it, anyway, so here's our old friend 79K14110 sheet A-1 once again, and this time I've colored up the Key Plan down there in the lower right of the drawing just above the Title Block, to give each of our five sides their own color, so as you can see how it all fits together with Side 2 now sitting inside of the new Side 5 they created when they welded their nice new RSS onto the existing FSS.

Phew.

That was quite a lot, wasn't it?

So now that we've got that sorted out, we'll start off with Elevation A on 79K24048 sheet S-51, which is cut from sheet S-50 (as are all of the other elevation views, and one section cut, we're going to be visiting here with this, so maybe go back and open up the plain unmarked version of 79K24048 sheet S-50 in another tab and kind of keep it there so you can flip back and forth so as you won't get lost along the way, and will always know exactly what you're looking at, and exactly where you're looking at it from), and which is showing us things from a point of view west of the FSS, looking back toward the tower to the east of us, looking at FSS Side 3.

And we see in our highlighted Elevation A on 79K24048 sheet S-51 where the access stair from the Centaur Platform comes down to FSS Elevation 120'-0" over on the left side, and and the Platform itself is held up with some substantial diagonal bracing underneath it, and it also has a rectangular frame up above it, which ties to the FSS just below 140'-0", and then, if that's not enough, farther up on the FSS, up at the 160'-0" level, there's yet another piece of Platforming, and tucked in underneath that, there's something called a "Drop Weight Assembly Framing (By Others)", and what the hell is that thing, and the main body of the Centaur Platform itself at 124'-3" along with all of its framing and bracing above and below is threaded out there right into the middle of the Struts... and all of a sudden, we're seeing that this thing is substantial, and how are they going to work it into those Struts without banging into something anyway, and what the hell is a Drop Weight Assembly, and...

...ok, it's looking like we're in for a little ride with this stuff.

Ok. Fine.

Let's look at FSS Side 2. This is where the Centaur Platform butts up against the south side of the FSS, cut as a section, from S-50.

So here comes Section C (not an "Elevation" which looks at things from the outside, but a "Section" which slices right through something, letting us see its innards in cross-section with our X-ray eyes) showing us the north side of our new Centaur Platforming, highlighted on 79K24048 sheet S-51.

And the north side of the Centaur Platform, being raised up above the main 120'-0" Primary Framing steel of the FSS, is getting into the big Primary Framing Pipe Diagonals on the south side of the FSS, that slope upward from each corner of the FSS, to the center of the Primary Framing Steel up above at the next main level at 140'-0", so they ran their main span over on that side, between the two Pipe Diagonals, and supported it on posts that rest on the main FSS 120'-0" perimeter wide flange, but on either side of the Pipe Diagonals, they stepped the edge of the Centaur Platform back just far enough to clear those pipes, and used much lighter steel to complete things, and it's tricky looking at all of that in the Section cut, but it's there and you can also see where they had to cut the FSS Side 2 handrails down, just underneath the Centaur Platform, and rework them so as nobody would go over the side through the space between the 120'-0" level of the FSS and the Centaur Platform sitting just above it at elevation 124'-3".

And that's the north side of the Centaur Platform, and it's a bit tricky, but it's straightforward enough.

And then we go to a highlighted look at the south side of the Centaur Platform with Elevation B on 79K24048 sheet S-51, and it all goes to hell as far as maintaining the protocols of sections and elevations, and once again we find ourselves dealing with yet another manifestation of odious PRC/BRPH Horseshit Engineering, where they just kind of slapped at it, looked at what they slapped together, shrugged their shoulders, said "Good enough," and moved on to the next thing they were going to be slapping at. Sigh.

To start with, Side 5 runs at an angle to everything else in this area, and they're telling us that Elevation B is showing us Side 5, but when we go back to S-50 to see where they're calling it from, we make the horrified discovery that they're aligning it squarely with Side 2, east/west aligned, looking at the Centaur Platform square-on, and not at the angle which Side 5 runs along, and when we look for the little circles with the letter 'B' in them above 'S-51' to tell us where to go to see it, we can't help but notice that the little arrows touching the bottoms of those circles are connected via a widely-broken line which cuts through things some damn where between the Hinge Column and the south side of the Centaur Platform, cutting directly across the goddamned Struts and the Lower Bearing Access Platforms as it does so, which, god DAMN it, now makes it a fucking Section, and not an Elevation, and then, if that isn't bad enough, we look closely at Elevation B and we can see, clearly, that they have gone to the additional trouble to show us those parts of the Centaur Platform which are behind the Hinge Column, Struts and Bearing Access Platforms in phantom view, thus placing our point of view, someplace south of the Hinge Column and Struts, giving the lie to where they drew their damnable line connecting those little circles with the 'B' and 'S-51' in them, and...

Christ amongus, what IS it guys?

And while we're at it, where is it?

And we work our way through it by inference, and in this case it does not seem to be any kind of life threatening, but let me tell you, that was definitely not a given, and seeing crap like this here, gives me a case of the Galloping Collywobbles wondering what might be lurking unseen... there.

So we tread gently was we go with this stuff, 'cause they've just fucking laced it with no end of pitfalls, inconsistencies, and hidden... things.

But still and all, despite the ongoing issues we find ourselves having to grapple with as regards the renderings of things, the Platforming itself remains pretty straightforward, and they've managed to thread it through the Struts well enough, so let us now go to Elevation D on 79K24048 sheet S-51, and give the front end of things a look, over on the east side, FSS Side 1, which of course is the side that faces the Space Shuttle, and which is also the side that we're going to be bolting our Porch onto.

And here, at last, we see that they finally wound up having to do something about those goddamned Struts, and what they did was to put three separate segments of 14"Ø pipe in there, with nasty curved coping cuts to get them to fit onto the existing pipes that were already in there, and okey and dokey, it's looking like somebody will have to do a little geometry to figure out how to make those cuts so as they will fit the existing Struts, and how hard can it be for a smart guy like you, anyway?

...well...

Take a look at this.

And what you're seeing in that photograph (provided by yet another Anonymous Benefactor) is RSS Primary Framing, and you're down at the lowest main level of the RSS (and I do not know if this is Pad A or Pad B, so I cannot use elevations), down at the APS Servicing Platform level, and you're looking at Column Line B, and that's a 12ӯ pipe which runs from Column Line 5 up toward Column Line 4.3 at the PCR Main Floor level, and that might not be quite a full half inch of deflection in there underneath the straight-edge that's being rested against its underside, but then again, maybe it is, and either way, that's a LOT of deflection in there, and if you had been told to come along and weld another heavy structural pipe to it, and you'd used what the drawings were telling you about sizes and locations, to calculate the correct cuts for your new pipe...

...well then...

...that wouldn't work out very well at all, would it?

And yeah, the drawings are horseshit, but the structure itself is horseshit, TOO!

And oh the fun you'll have costing up a job like this, coming in low bidder, getting the job, and then having to figure out how to not go bankrupt while you perform the work, and you send NASA paper on shit like this, and they laugh in your face and tell you the bid documents clearly stated that it was the contractor's responsibility to verify all existing conditions, so tough shit bub, and now you're over budget and behind schedule, and...

...such jolly jolly fun it is!

So now that we've got the Platform itself all figured out, we can just kind of wander around in the drawings admiring stuff...

...and what's this?

What the hell is this on 79K24048 sheet S-52? Detail 'G' taken from S-50, which we already thought we'd seen and understood... completely.

Imagine how much fun it must have been to cut and fit that thing. And those are full penetration welds being called-out in there, and of course that always adds to the fun... with rigging... with fitting... with trimming... with hanging a float someplace that will let you even get to the goddamned thing with a welding rod... with the NASA QC Inspectors who come around to look at it once you're done... with everything.

Jesus fuck!

Struts.

And they keep calling it an "Incline" Structure, and what the hell is that, anyway?

RBUS, that's what.

Rolling Beam Umbilical System, and it sits at an incline, and...

I wish I had better drawings for this nightmare, I really do.

But I don't.

Here's what you get, in isometric view, the whole RBUS System, as a Pad A installation, in Figure 3, which is taken from Rolling Beam Umbilical System, by Bemis C. Tatem Jr., Planning Research Corporation, Kennedy Space Center, Florida, which you've already seen, more than once, but it's a good document, so you get to see it again right here. Please note that all subsequent RBUS System illustrations, unless otherwise noted, will also be taken from this same document.

And it's Pad A, so they're giving you the Pad A Elevation of 119'-3", (with FSS elevations to match) instead of the 124'-3" elevation we've been seeing up to now on our Pad B drawings. Otherwise, it's pretty much all the same thing.

And quite the "thing" it is.

They very helpfully keep the rendering of the RSS and FSS exceedingly spare and bare-bones, so as not to further confuse you visually with a swarm of extra lines, and also dispense with the bracing up above the main level of the Centaur Platform, as well as the access platforming that wraps around the back of the FSS behind that "Dropweight Module" (why can't they just pick one name to call something and then stick with it?), but it's all there, whether you see it or not.

Prior to the cancellation of the entire Shuttle Centaur Program, in the immediate aftermath of the Challenger Disaster, we built one of these RBUS things on Pad B, and I was standing right there on the Centaur Platform next to it when they did their first functional test of the Retract Mechanism (no MLP, no orbiter), but it turns out that it was a very camera-shy creature, and actual photographs of it, on either one of the Pads, are very rare.

Here's a photograph of it on Pad A that I found, taken by Terence Burke in August 1985, which he uploaded to a website I was previously unaware of, called unsplash.com, and it's freely downloadable, and all he wants is attribution, so yeah, thanks a million Terence, you came through with a good one, here.

Here it is again, labeled, to let you see the various elements involved with it.

So ok. So what the fuck is this thing, anyway?

Well... out on its business end, it's nothing more than a carrier plate which holds the LH2 plumbing and disconnects which interface with the Centaur LH2 plumbing in the Space Shuttle.

Here's that end of things, shown in Figure 7, and we can already see, as we zoom in for greater detail, that it's becoming more and more contrapted as we do so. I've never liked contraptions. I've never trusted contraptions. Too many little dingdongs and doojiggers all rattling around in there together, any one of which decides for no good reason to rattle around just a little bit wrong somehow, and all of a sudden, the whole thing is jammed, unworking, unworkable. Me not like. And when you combine contraptedness with something like the Space Shuttle, which carries live crew, and is gigantic, explosive, and already plenty-complicated enough in the first place... me really not like.

And then you step back a little farther, to see the whole thing, and...

...boy ...I dunno.

The Porch is already extended out there toward the Orbiter to an unpleasant distance, but it's not far enough and so they made themselves a nice RBUS to extend out toward the Orbiter even farther, to get all the way over there and touch it, and ok, ya gotta do what ya gotta do, but...

There's just something about the look of the goddamned thing.

Does not inspire confidence.

Doesn't really quite pass the smell test.

Just a little too flimsy and spindly looking.

Here's the whole RBUS in Figure 9, extended, but they're rendering it at the LETF (Launch Equipment Test Facility, and yeah, that's yet another really cool place, and at some point I've got to figure out how to introduce that into the narrative, but not now), which kinda waters it down visually, 'cause there's no Space Shuttle in there to help with grokking it.

So ok, so I took a slice out of Figure 4 (which is something they never built and no I'm not gonna show you explicitly, ya gotta read the damn PDF document and find it for yourself), and scaled it as well as I could (none of this stuff is fully correct, and all of it is not only different sizes, but it's also different aspect ratios, and there's no end of sneaky distortions introduced thereby, and... we'll just have to do the best we can with it), and here's Figure 9 again, with a nice blue Orbiter overlain on the LETF stuff. And if you look close, in blue, you can see "Drift Curve" and it's a line that does not go "straight up" but kind of veers off toward all this ridiculous hardware a little, and they're telling you with this thing that they're fully aware that the Orbiter does not go "straight up" when it takes off, but instead, there's a bit of an envelope that it can make excursions within, maybe the wind was swirling around a little more that day than usual, or maybe something else, who knows, and... it's all pretty fucking close in there, and wouldn't it be a shame if the fucked-up RBUS was to have some sort of Contraption Event, and it jammed, and was unable to get out of the way, and shit like this is what wakes you up in a cold sweat at 3:00am, and sometimes you can fall back to sleep, and sometimes you can't, and either way, come the dawning of the next day, you go right back out there and work on it some MORE.

And if you think I'm maybe overplaying it a little with this "cold sweat" talk, well then, you've never been anywhere like this and I hope to god you never wind up anywhere like this in the future, because it got to not only me, but it got to KAI, my goddamned son, and we were just talking about this kind of stuff on the phone last week, and both of us, for the full duration that I was out there working on this crap, and thenceforth too, had recurring nightmares about it. Recurring nightmares where the Shuttle would not make it, taking off or landing, and god DAMN, but this shit just eats away at you, and you... LIVE WITH IT. And whenever the thing flies, you're standing there watching it, and there's a piece of you that has seen and remembered every single nightmare, and you love what you're doing, and the Space Shuttle is just the coolest fucking thing on the whole planet, but... not everybody came home every time, and you feel that shit down in the pit of your stomach... Every. Single. Time.

And we can look a little closer at our contraption, using Figure 6 in Bemis' swell document, and...

Ok, why not, here's the Rigging diagram for it, which we can see on Page 14, Figure 10, and now the Dropweight is getting into the act, and it's the Dropweight which propels the Rolling Beam when it gets snatched away from the Orbiter at T-minus zero when the Holddown Bolts get blown and the SRB's explode irreversibly into action, and...

That Dropweight, all by itself, was quite the substantial item, and here you go, Figure 8 on Page 11, and yeah, it really is over three stories tall, and...

And this thing just keeps getting more and more and more whack...

And we were standing there on the Platform, kind of someplace between the Dropweight Assembly and the Rolling Beam itself, and over by the handrail on the south side of the Platform, trying to get as far away from all of it at the same time as we possibly could, and it's Functional Test day, and you're there as one of the Designated Representatives, and part of you thinks it's all really cool, and another part of you is wondering if this thing that you're so very close to is going to kill you, and there's a pretty good crowd of people out there on the Platform grating between the FSS and the RSS, and most of 'em wanted to get closer to it, but we didn't trust the fucking thing, so ok, so you guys can all stand right there between us and all the contraptions making up this thing, and we were joking about specifying gold for the Dropweights, 'cause of course gold is nice and dense, and makes for a more compact and elegant solution to that aspect of things, but no, nobody could figure out how to get a few tons of gold past the engineering review hierarchy, and ok, now they're counting it down, and we got quiet, and BANG, shingshingSHINGSHING the fucking thing springs into full and vigorous life and here comes the Beam, sucking back into the Incline framework, and there go the Dropweights, plummeting downward in their Support Frame, and it ends with a THUD, and it all grows still and quiet again, and the assembled crowd all becomes animated again, all at the same time, and no, there was no applause at the goddamned thing, but everybody was very happy that it worked, and a few of us were very happy that it didn't kill us, and...

Fill up the Centaur with a railroad tank car load of psychotically explosive LH2 via the long skinny pole affair extending out from the end of the main RBUS body, extending all the way out to the side of the Shuttle's fuselage where it would meet the plumbing which would then take that liquid dynamite and pump the Shuttle full of it in a place where such stuff was never intended to go, inside the fucking Payload Bay fer chrissakes, leave it stuck to the side of the Shuttle for the requisite fill, drain, and venting work that proceeded all the way down to T-minus zero, with main engines blazing away for six long seconds coming up to full thrust and the whole stack rocking back and forth in full twang mode, and then pray to the little baby jeesus up in the sky that A.) there wouldn't be a problem with the RBUS such that it hangs up, in place, and gets smashed into by the left side of the Orbiter as it was rising away from the MLP, and B.) the goddamned Centaur itself wouldn't develop some kind of nightmare issue, locked inside the payload bay, unjettisonable for the full length of the uphill climb into orbit.

Sure. Sounds great! Let's do it!

And by god they were doing it, but they never got their chance with the thing.

I mourn the loss of mission 51-L to this day, but I fear had it flown, I would have wound up mourning the loss of a different mission later, one that flew with a fully-loaded Centaur on board.

So yeah, the fucking thing was never meant to be, and the fucking thing never happened.

None too very long afterwards I was gone, down the road to slay A Dragon Most Fell at Complex 41, and I wasn't there when they took all of the mechanism parts of it off of the tower, leaving the Platform and Porch behind as a sad (and very frightening) reminder of "What might have been."

And we move on to our fourth and final image on this page, looking back in time, seeing a bright-eyed six-year-old standing in a place beyond imagining, beyond happy to be there.

This is an unusual view of the Pad, there in the background behind Kai, from a standpoint of both the angle we're looking at it from, as well as the backed-out zoom, which allows us to get a fair decent sense of the body of the Pad, with the Pad Slope and Crawlerway extending out of frame to the right, and just a bit of Access Road 'E' sloping down and away from the top of the Pad on the opposite side.

Kai speaks for himself, but there are a few items of note with the facility itself, despite the image resolution being pretty poor quality for making out those more-distant items.

This is the only image I have which shows us anything at all about what's going on with the southern end of the Lightning Wire shown in general arrangement on 79K10338 sheet S-3, which stretches 1,000 horizontal feet south, and just under 400 vertical feet up (and across the top of the Lightning Mast) from its northern terminus, and then across another 1,000 horizontal feet, and back down to the surface of the Pad, where it ends on the Pad Slope, to the right of Kai's shoulder, so we're going to use it, despite the fact that it's far less than optimal for the job.

Here's a Google Earth image of Pad B taken in 2006, marked up to let you see the distant slope of Access Road 'E', the viewpoint location where I was crouched down to get Kai's head and shoulders up into the levels of the Pad, and a teency weency little octagonal (yes, you can tell when you look at the photograph of Kai, if you look close) Grounding Pad shown on 79K10338 sheet E-36 detail 'D', where the Grounding Cable comes off of the main Lightning Wire and drops vertically into a surprisingly complicated copper affair sitting on top of a very specifically non-steel-reinforced 6-inch thick concrete slab sitting on the rest of the support, which allows them to be good and goddamned sure that any lightning strikes which find the Lightning Wire will be safely and reliably taken to ground exactly where they want them to, thereby dissipating them safely, so as we maybe don't go blowing up the Space Shuttle by accident when it's sitting there on the MLP when Florida Weather comes calling. Surrounding the Grounding Pad, a quartet of Warning Signs on white PVC posts are clearly visible in Image 085, and you can see them on the same drawing, E-36, in Detail 'G'. Detail 'C' on that same drawing, shows us the Grounding Wire dropping vertically to the Grounding Pad from the main Lightning Wire and that too is visible in the photograph, but only just.

Regards the Lightning Wire, I can speak from personal experience, and we were up on the Pad Deck one day, doing some damn thing or other, out there between the RSS and the Flame Trench, out in the open, and it was one of those hot days in Florida where you get a cumulus cloud buildup that starts out early with the most benign little puffy white things you can imagine, backed by a Cerulean Blue Sky, that slowly coalesce and morph over time into towering cumulonimbus monsters blotting out the sky above the western horizon, black and evil-looking on their bottoms, with feathery white wisps of flat anvil-top extending nearly to the zenith, and those things mean business, and you respect them, but before they've turned into monsters, it's just a bunch of separated gops of white cotton with flat dark bottoms, but no rain, no sensible weather of any kind, and that's what it was like that day, and OUT OF NOWHERE, from one of those small white separated gops of cotton, CRACKOWWWSHH, and the fucking thing was essentially directly over our heads and how something that small and that low-key could have managed to juice itself up to the point where it could throw such a violent thunderbolt straight down at us like it did, I'll never know, but it was a fucking Direct Hit and it would have killed us all, except that the Lightning Wire intercepted it 300 some-odd feet over our heads, and we all just about jumped out of our skins, looked around, realized that nothing had happened to any body or any thing, and we looked at each other, exchanged a few low swear words, and got the hell out of there!

So yeah. Speaking from personal experience, I can swear and declare that the Lightning Wire works, and it's a damn good thing it does, too.

You would think that whatever it was that held over 2,000 feet of tightly-stretched stainless-steel wire rope in place would be quite a bit more substantial visually than whatever it was that the Ground Wire dropped to, but you would be wrong, if you did.

Most of that thing is below the surface, and the part that sticks up above the concrete skin of the Pad Slope turns out to be pretty innocuous looking, and it's visible in the photograph too, but... not a whole lot going on with that part of things that you can see, aside from the fact that it's a noticeable distance south of the Grounding Pad. Drawing 79K10338 sheet S-43 tells us all about that thing, and the one on the north end of the Wire too, and tells us how to rig the whole 2,000 foot-plus length of the Lightning Wire, too.

Up on top of the Lightning Mast, there's other interestingness with the Lightning Wire, and we'll do that stuff too, but not yet. Not now, ok?

And we'll close our Family Day at the Pad for the landing of STS-41G, with another look at the photograph of Kai with Pad B behind him, marked up to show you where all this stuff is located.

We've done pretty good for ourselves out here today. Let's head on back home now, ok? I'm starting to get hungry.

Return to 16streets.comACRONYMS LOOK-UP PAGEContact Email Link |